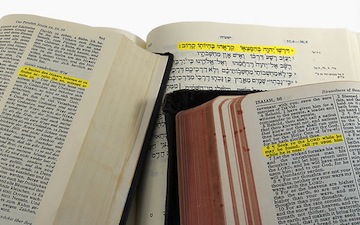

When the King James Version (KJV) was the only game in town, it must have been nice to have everyone literally “on the same page” during corporate Bible study. Things couldn’t remain that way, however, because the KJV was translated using only 16 original language manuscripts and today we have uncovered 1000‘s, many of them older and better than those original 16.

When the King James Version (KJV) was the only game in town, it must have been nice to have everyone literally “on the same page” during corporate Bible study. Things couldn’t remain that way, however, because the KJV was translated using only 16 original language manuscripts and today we have uncovered 1000‘s, many of them older and better than those original 16.

By the time I was in seminary in the late 90’s, there were what I considered to be three real options: the Revised Standard Version (1952), the New American Standard Version (1971) and the New International Version (1978). I had grown up with the RSV but in Evangelical circles this version was suspect because it sought to incorporate liberal critical theory into the translation process (although many of my most conservative professors preferred the RSV and I continued to use it during seminary and for a time afterwards). As I began to preach regularly, I realized the RSV was not going to catch on in my particular church environment and figured it was not wise or helpful to continue to be out of step with the congregation. The NIV and the NASB provided two fairly different but widely accepted options. The NIV was created by translators leaning more to towards the “dynamic equivalence” translation philosophy, which seeks to re-say what the original text says in words and phrases that are natural to the host language. Dynamic equivalence translations are also more likely to make interpretive decisions in texts where the original language might be ambiguous (although most translations end up doing this because the host language sometimes has no easy way of maintaining the ambiguity). Such interpretive decision-making is why it matters on some level what the beliefs of the translators are. At any rate, this philosophy of translation resulted in a punchy, readable rendering of the original languages and I chose to use it because of its natural English feel and accessibility. Besides, I’d be studying with the original languages on hand and so would be getting the full breadth of translation possibilities. The NASB, on the other hand, was written with a bias for “formal equivalence” (sometimes inaccurately referred to as “word for word”). Formally equivalent translations can sound very wooden in English or even unintelligible as they seek to carry over the lexical and grammatical forms of the original language into the host language. But if translation is about making something intelligible, there is no guarantee that simply reproducing these forms makes it more intelligible; sometimes it has the opposite effect. So, in my mind, advantage NIV.

In the last decade, the translation options have further multiplied. The RSV was revised to become both the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV, 1989) and the English Standard Version (ESV, 2001). Then came the New Living Translation (NLT, 2004), Today’s New International Version (TNIV, 2005), the New English Version (NET, 2005) and soon a revision of the NIV (2011, available online now). All these versions attempt to solve two primary translation problems: 1) how best to balance formal/dynamic equivalence translation philosophies and 2) how best to incorporate cultural changes in gender related language use. The NRSV is an update of the RSV emphasizing the use of gender inclusive language. Many have documented how some NRSV gender inclusive language decisions create theological confusion in places and so the NRSV has not been generally considered in Evangelical contexts. The ESV is also a revision of the RSV, striving to maintain a balance between dynamic and formal equivalence, but with a more conservative approach to usage of gender inclusive language (it does use gender inclusive language). The NLT is perhaps furthest on the dynamic equivalence side and, while certainly worth consulting, is not generally considered for corporate congregational use. The TNIV was a revision of the NIV that has already gone out of print due to controversy regarding its gender inclusive language choices. While this text was heavily criticized by the broad evangelical world, many conservative Biblical scholars who are highly trained in translation theory continue to hold the TNIV in high regard. In surveying the debate about the TNIV it seems that while it started as a discussion among the faithful about the technicalities of gender inclusive translation theory, it ended as a somewhat politicized dispute with the majority of evangelical leaders (whether or not they were schooled in science of translation) siding against the TNIV. While I’m not in a position to give a final ruling on that debate, it is now a mute point because the TNIV is out of print. A new revision of the NIV is due out in 2011 and will include a reassessment of all the passages that lead to the controversy. In the meantime, however, huge numbers of Bible readers have switched to the ESV which intends to be both faithful and readable and, as mentioned, has dealt more conservatively with the gender inclusive language question. In addition, the publishing of the ESV Study Bible in 2008, complete with comprehensive exegetical and theological notes, has further boosted the ESV’s appeal.

Sorting it all out, it would seem that, going forward, the 2011 NIV and the ESV remain the most generally accepted options. The question for a pastor in the daily grind of preaching and shepherding is two-fold. 1) Will the 2011 NIV be “better” than the ESV and 2) will it catch hold enough? The second question is hard to predict given the response to the TNIV and the move of many to the ESV. We won’t know for some years now. With respect to the first question, however, the 2011 NIV is available online now and can be compared to the ESV. So far, the conclusion is the same one that we get so often in biblical translation: each translation is better than the others in some ways and not in others. I don’t particularly like, for example, that the NIV has stayed with translating “flesh” as “sinful nature” (although, after an in-depth reading of the rationale behind it, I have a much greater respect for this decision). In other cases, it seems the 2011 NIV takes a more consistent approach to the inclusive language problem (cf. Hebrews 2:11 and 3:1 in ESV and 2011 NIV, for example). On balance, however, I moderately prefer the overall philosophy of the ESV (generally seeking to “interpret” less, maintain ambiguities and leave more for the reader to figure out). I can live with its imperfection (but I could live with the imperfections of the 2011 NIV and many of the other translations as well).

In all this, it is crucial to keep several points in mind. For the past months, I’ve been doing devotions and studying with four or five versions in parallel plus the original language text and have come to this conclusion: no translation is perfect. But, since I can’t mix and match my Bibles on the fly, I have to choose one. On balance, I choose the ESV. At the same time, I/we must remember what a luxury it is to choose! Instead of 16 lower quality manuscripts as was the case with the KJV, the Bible I read is based on 1000‘s of manuscripts, many of them of extremely high quality. Not only that, generations of scholars have combed through these manuscripts and wrestled deeply to determine the best way to express in English the words of the original language. This is a luxury very few Christians in history have had. Lastly, we shouldn’t be put off by all the different versions and their accompanying philosophical differences. What this says is that we are a people who take the word of God very seriously. We want to know it faithfully. We want to read it in the best possible way. As long as that remains true, we can only be hopeful.

I have been doing the same searching for the last 10 years. Just when I think I have it figured out, I pick up a different translation and think that one says it better. I grew up with the KJV but seldom read it on my own because it used language that I didn’t. When the Living Bible paraphrase came out, I read it a lot. When the NIV came out in 1978, it became my primary Bible for the next 20+ years. It was translated by conservative evangelical scholars and was word for woed until it came to a place where word for word for word made no sense in Englsh, then it used an English equivalent (Amos 4:6 comes to mind). The bottom is that there is not one translation that is the best for everyone. For tose trained in original languages, why even bother with an English translation? Or if you do, then use the most literal (NASB) and explain to the folks what it really means. For those with English as a second language, probably the NLT or NIRV. For most of us, however, the NIV is probably the best ‘middle of the road’ translation for conservative evangelicals. It is the one most people use, so people are familiar with it and would probably read it. My problem with the ESV is it’s awkward English. Like you said, no translation is perfect, but if you are going to pick one to use not only in church settings but also in reaching people with no Christian background, a translation like the NIV. Something is always lost in translation. That’s what pastors and professors are for! I would stick with a translation that’s as literal as possible but also readable in English. For me, that’s the NIV. Anyway, my two cents worth.

Very graciously written, much like your preaching Pastor Andrew. As for myself, it begins (but doesn’t end there) with how each version translates Is 7:14. Is the verse referring to a virgin or a young maiden, sometimes young woman. Jewish scholars will argue that this verse is not a messianic prophecy relating to the virgin birth of Jesus quoted in NT Gospel of Matthew (Matt 1:20-23) because the Hebrew word ALMAH is literally young woman. RSV & the NET Bible (not to be confused with NEB, New English Bible) does not render the Hebrew to virgin but young woman, although for the NET (recommended by Swindoll) will give much footnotes about the controversy. Good primer for Bible translations can be found here: http://bible.org/seriespage/part-iv-why-so-many-versions

My in-laws bought my wife and me mhtnaicg ESV study Bibles for Christmas and we have been reading/studying from it primarily this year. Loving it! I grew up with King James, I read it in my youth,I read it in my Sunday school,It’s how I learned the truth (bonus points for anyone who can name that tune)But then I got into Bible bowl at age 12 or so and discovered NIV. Spent years and years there, then I realized I was allowed to read other translations. My wife just bought me a pocket-sized Holman Christian Standard Bible a week ago Saturday and I’m loving it, too!So now my favs are (in no particular order) ESV, NLT, NASB, NCV, HCSB, and the old standby, Mr NIV (I actually got to where I didn’t care at all for the NIV, but I think I was just burned out on it). I also dig the Message. I’ll have to try God’s Word version.Great post. May I steal your idea, Trey?

Literal translations are an excellent resource for serious Bible study. Sometimes the meaning of a verse depends on subtle cues in the text; these cues are only preserved by literal translations.